Last week, the interminable 2020 U.S. presidential election entered a new phase as 20 Democratic candidates over the course of two nights debated each other in Miami, Florida. Here, I’ll note some of the key policy positions staked out by the candidates during the debates.

Night One (Video, Transcript)

Candidates: Senator Cory Booker, former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, former Representative John Delaney, Representative Tulsi Gabbard, Washington Governor Jay Inslee, Senator Amy Klobuchar, former Representative Beto O’Rourke, Representative Tim Ryan, and Senator Elizabeth Warren.

Immigration

Julián Castro pledged to immediately end Donald Trump’s zero-tolerance, remain in Mexico, and metering policies. He also said he would pass an immigration reform law within 100 days “that would honor asylum claims, that would put undocumented immigrants—as long as they haven’t committed a serious crime—on a pathway to citizenship.” He also supported “a Marshall Plan” for El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, and called for the repeal of section 1325 of the Immigration and Nationality Act, which makes crossing the U.S. border without documentation a criminal offense.

In perhaps the most memorable moment of the night, Castro criticized Beto O’Rourke for failing to include the repeal of 1325 in his immigration policy. O’Rourke supported citizenship for DREAMers, called for a “family case management program” rather than detaining families, and backed investment “in solutions in Central America.” O’Rourke said that he introduced legislation in Congress to decriminalize crossing the border for asylum-seekers, but did not commit to applying this standard to all undocumented people.

Cory Booker said that as president he would re-instate DACA, preserve Temporary Protected Status (TPS), make “major investments in the Northern Triangle,” and end ICE raids across the U.S. that separate undocumented immigrants from their families. Jay Inslee said that immigrant and refugee children should be released from detention pending their hearings. Tim Ryan expressed support for repealing section 1325, while Amy Klobuchar supported returning to the 2013 immigration bill as the starting point for future legislation.

Climate Crisis

Inslee brought up green jobs during a discussion of the economy, saying, “we know that we can put millions of people to work in the clean energy jobs of the future.” Ryan added, “[w]e need an industrial policy saying we’re going to dominate building electric vehicles, there’s going to be 30 million made in the next 10 years. I want half of them made in the United States. I want to dominate the solar industry and manufacture those here in the United States.” Elizabeth Warren continued, “[w]e need to go tenfold in our research and development on green energy going forward. And then we need to say any corporation can come and use that research. They can make all kinds of products from it, but they have to be manufactured right here in the United States of America.”

Later in the debate, the moderators turned the discussion to climate change directly. Inslee said addressing the climate crisis should be “the top priority of the United States, the organizing principle to mobilize the United States” and promised to “put 8 million people to work.” O’Rourke pledged to “fund resiliency” in U.S. communities on the frontlines of climate change, “mobilize $5 trillion in this economy over the next 10 years,” and pay “farmers for the environmental services that they want to provide.” He said these steps would prevent an additional 2 degrees Celsius of global warming. Castro committed to re-joining the U.S. in the Paris Agreement on climate. John Delaney supported a carbon tax plan which would include “a dividend back to the American people.”

Criminal Justice

Booker said, “our country has made so many mistakes by criminalizing things—whether it’s immigration, whether it’s mental illness, whether it’s addiction.” Castro claimed that he is “the only candidate so far that has put forward legislation that would reform our policing system in America.”

Foreign Policy

In a show of hands, all candidates except for Booker indicated that they would bring the U.S. back into the Iran nuclear agreement “as it was originally negotiated.” Booker said that the U.S. should not have pulled out of the deal as it was, but as president he would negotiate a better deal if he had the opportunity. Klobuchar said that she would ask Congress to authorize military force before entering into a conflict. Tulsi Gabbard opposed war with Iran.

Later in the debate, moderator Lester Holt read a viewer question: “does the United States have a responsibility to protect in the case of genocide or crimes against humanity? Do we have a responsibility to intervene to protect people threatened by their governments even when atrocities do not affect American core interests?” O’Rourke answered, “yes, but that action should always be undertaken with allies and partners and friends.” Bill de Blasio argued that the U.S. “should be ready” to intervene in the case of genocide, “but not without congressional approval.”

Ryan suggested that he supports U.S. troops remaining in Afghanistan, while Gabbard called for troops to be withdrawn.

Healthcare

In a show of hands, de Blasio and Warren indicated that they supported abolishing private health insurance. Warren made clear that she is “with Bernie on Medicare for All.” Booker also supported Medicare for All, while Klobuchar, Delaney, and O’Rourke spoke out against abolishing private insurance.

Castro affirmed that his healthcare plan would cover abortion, and said he “would appoint judges to the federal bench that understand the precedent of Roe v. Wade.” Inslee said that insurance companies should not be allowed to deny coverage for abortion. Warren said that she would ensure “that every woman has access to the full range of reproductive health care services” including abortion and birth control. She also supported making Roe v. Wade a law.

Economic Policy

Klobuchar supported free community college; a doubling of Pell Grants ($6,000/year to $12,000/year) and expansion of who qualifies to include “families that make up to $100,000.” O’Rourke dodged a question about whether he supports a 70% marginal tax rate but pledged to tax capital at the same rate as other income and raise the corporate tax rate to 28%. Booker said he would “appoint judges that will enforce” anti-trust law and direct the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission to check corporate consolidation. Castro supported the Equal Rights Amendment and “legislation so that women are paid equal pay for equal work.” De Blasio called for “a 70 percent tax rate on the wealthy,” free pre-K and public college, a $15 minimum wage, and breaking up large corporations “when they’re not serving our democracy.” Delaney supported “a doubling of the earned income tax credit, raising the minimum wage, and creating paid family leave.” Inslee said he has “a plan to reinvigorate collective bargaining.”

Gun Violence

Warren supported universal background checks, banning “the weapons of war,” and conducting additional research on how to achieve greater safety considering the guns already present in communities. Castro said that he would support bypassing the filibuster in the Senate if necessary to pass gun reform. Ryan called for “trauma-based care in every school” to prevent violence committed by young people. O’Rourke indicated support for universal background checks, red flag laws, and banning the sale of assault weapons. Klobuchar said that she supported an assault weapons ban as a prosecutor. Booker proposed requiring licenses to buy guns. De Blasio stated, “if we’re going to stop these shootings, we want to get these guns off the street, we have to have a very different relationship between our police and our community.”

Night Two (Video, Transcript)

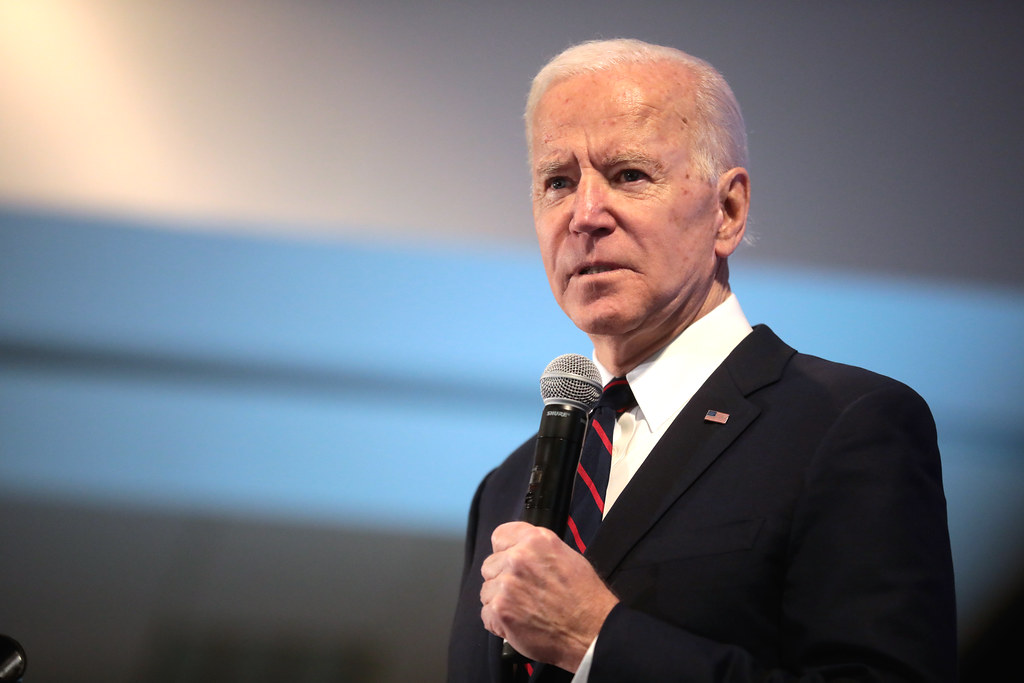

Candidates: Senator Michael Bennet, former Vice-President Joe Biden, South Bend, IN Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, Senator Kamala Harris, former Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper, Senator Bernie Sanders, Representative Eric Swalwell, author Marianne Williamson, and former tech executive Andrew Yang.

Racial Injustice

Probably the most significant moment of the night was an exchange between Kamala Harris and Joe Biden in which Harris challenged Biden’s recent statements and political history on segregation. Harris said to Biden, “it was hurtful to hear you talk about the reputations of two United States senators who built their reputations and career on segregation of race in this country. And it was not only that, but you also worked with them to oppose bussing. And you know, there was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bussed to school every day, and that little girl was me.” Biden said that Harris had mischaracterized his position, adding, “you would’ve been able to go to school the same exact way because it was a local decision made by your city council.” Harris asked Biden, “do you agree today that you were wrong to oppose bussing in America then?” Biden responded, “I did not oppose bussing in America. What I opposed is bussing ordered by the Department of Education.” With Biden making clear that he had opposed federal action to desegregate schools through bussing, Harris made the classic progressive argument that states’ rights should not be used as a cover to protect injustice.

Following the police shooting of Eric Logan, a black man, in South Bend, Indiana, moderator Rachel Maddow asked Pete Buttigieg why the number of black police officers had not increased under his watch as mayor (Maddow noted that the police force is “6 percent black in a city that is 26 percent black”). Buttigieg responded, “[b]ecause I couldn’t get it done.” He continued, “until we move policing out from the shadow of systemic racism, whatever this particular incident teaches us, we will be left with the bigger problem of the fact that there is a wall of mistrust put up one racist act at a time.” Eric Swalwell said that Buttigieg should have fired the chief of police, and John Hickenlooper claimed that during his time as mayor of Denver, the city accomplished what South Bend has not. He said, “I think the real question that America should be asking is why five years after Ferguson, every city doesn’t have this level of police accountability.”

Marianne Williamson supported reparations for slavery, and Michael Bennet said that “the attack on voting rights in [Supreme Court decision] Shelby v. Holder is something we need to deal with.”

Economic Policy

Bernie Sanders called for free public college, and the elimination of student loan debt to be paid for by “a tax on Wall Street.” Biden pledged to “make massive cuts” in tax loopholes and end “Trump’s tax cuts for the wealthy.” On education, he said he would triple spending for Title 1 schools, implement universal pre-K and free community college, and freeze student debt and interest payments for people earning under $25,000/year. Harris committed to repealing the 2017 Republican tax law and providing a tax credit of “up to $500 a month” to families making under $100,000/year. She also called for a “middle class and working families tax cut.” Buttigieg supported “free college for low and middle-income students for whom cost could be a barrier,” the ability to refinance student debt, and raising the minimum wage “to at least $15 an hour.” Andrew Yang supported a universal basic income plan to provide payments of $1,000/month, which would be paid for in part by implementing a value-added tax. Kirsten Gillibrand called for “a family bill of rights that includes a national paid leave plan, universal pre-K, affordable daycare, and making sure that women and families can thrive in the workplace no matter who they are.”

Healthcare

Sanders supported Medicare for All and committed to reducing prescription drug prices by 50%. Hickenlooper and Bennet opposed abolishing private insurance. Bennet supported the Medicare X plan. In a show of hands, only Sanders and Harris indicated that they would abolish private insurance (Harris said on Friday that she had misheard the question and clarified that she favored Medicare for All without abolishing private insurance). Gillibrand emphasized that the Medicare for All plan would have a transition period to single-payer. She suggested that private insurance companies could try to compete with the government health plan, but likely would be unable to do so successfully. Buttigieg supported a “Medicare for all who want it” plan. Biden advocated building on Obamacare and providing an accessible plan similar to Medicare on insurance exchanges. He also said that the government should negotiate drug prices for those on Medicare, and called for jailing insurance executives for misleading advertising, “what they’re doing on opioids,” and bribing doctors. In a show of hands, all candidates indicated that their healthcare plans would cover undocumented people in the U.S.

Sanders said, “a woman’s right to control her own body is a constitutional right” and pledged to only appoint justices to the Supreme Court who support Roe v. Wade. He asserted, “Medicare for All guarantees every woman in this country the right to have an abortion.” Gillibrand opposed the Hyde Amendment and said she would “guarantee women’s reproductive freedom” when making deals as president.

Immigration

Buttigieg commented, “[t]he American people want a pathway to citizenship. They want protections for DREAMers. We need to clean up the lawful immigration system… And as part of a compromise, we can do whatever commonsense measures are needed at the border.” Harris committed to reinstating DACA, deferring deportation for veterans and parents of DREAMers, eliminating private detention centers, beginning “a meaningful process for reviewing the cases for asylum,” and releasing “children from cages.” Hickenlooper called for ICE to be “completely reformed” and said there should be “sufficient facilities in place so that women and children are not separated from their families. The children are with their families.” Williamson criticized the other candidates for not discussing U.S. foreign policy in Latin America. Gillibrand said, “I would reform how we treat asylum-seekers at the border. I would have a community-based treatment center,” provide lawyers to asylum-seekers, and utilize judges who are “not employees of the Attorney General but appointed for life.” Gillibrand also said she “would fund border security,” stop funding private detention centers, and support “comprehensive immigration reform with a pathway to citizenship.”

In a show of hands question, Buttigieg, Gillibrand, Harris, Swalwell, Williamson, and Yang indicated support for making border crossing a civil rather than criminal offense. Bennet did not raise his hand, Hickenlooper’s position was unclear because the camera moved away from him, while Biden and Sanders pointed a finger, presumably indicating that they wanted to elaborate on the question. Later, Biden said he would reunite families who have been separated and send “billions of dollars worth of help to the region immediately.” When pressed by moderator José Díaz-Balart, Biden said that an undocumented person who had not committed any crimes “should not be the focus of deportation.” He also said the U.S. “should immediately have the capacity to absorb” asylum-seekers and “keep them safe until they can be heard.” Sanders said he would “rescind” all Trump policies on immigration and convene a summit with the presidents of countries in Central America. Swalwell opposed deporting undocumented people who do not have criminal records. Harris said she disagreed with President Obama’s policy “to allow deportation of people who, by ICE’s own definition, were non-criminals.” She emphasized that it is necessary for the victims of rape to be able to report the crime committed against them without fear of deportation. Bennet touted the 2013 immigration bill which he co-wrote.

Gun Violence

Swalwell committed to a “ban and buyback of every single assault weapon in America.” Sanders called for universal background checks, an end to the gun show loophole and straw man provision, and a ban on assault weapons. When pressed by Swalwell, he appeared to support the buyback of assault weapons as well. Harris said she would give Congress 100 days to pass gun legislation, and take executive action if the deadline passed. She supported background checks, a ban on the importation of assault weapons, and said she would require the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms to take the licenses of gun dealers who violate the law. Biden called for smart guns that require a user’s biometric features and a buyback of assault weapons.

Climate Crisis

Harris supported the Green New Deal and re-entering the U.S. into the Paris Agreement. Buttigieg supported a carbon tax with a dividend that would be “rebated out to the American people in a progressive fashion.” He called for “the right kind of soil management and other… investments” in the rural U.S. and re-entering the Paris Agreement. Biden committed to building 500,000 new recharging stations to reach “a full electric vehicle future” by 2030. He supported re-entering the Paris Agreement and investing $400 million “in new science and technology.” Williamson supported the Green New Deal.

Foreign Policy

Bennet called for restoring relationships with U.S. allies. Sanders argued that it is necessary to rebuild “trust in the United Nations and understand that we can solve conflicts without war but with diplomacy.” Sanders opposed war with Iran, and said he “helped lead the effort for the first time to utilize the War Powers Act to get the United States out of the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen, which is the most horrific humanitarian disaster on Earth.” Gillibrand said she would “engage Iran to stabilize the Middle East and make sure we do not start an unwanted never-ending war.” Biden supported the withdrawal of combat troops from Afghanistan.